4 min

4 min

The Building Renovation Unit in Copenhagen (Denmark) supports renovation of the city’s existing building stock. At the head of this unit, Janus Christoffersen works on renewable energy projects aimed at drastically reducing the use of resources and limiting the city’s CO2 emissions. Here he shares his grassroots expertise.

What challenges do you believe the construction sector faces on the road to the energy transition?

The energy transition of the construction sector – i.e. equipping ourselves to reduce the huge consumption of energy and materials we see today – must be seen as a complex transformation requiring a vision shared by all stakeholders and over the long term. At European and national level, the EPBD1 and CSRD1 initiatives, although yet to be implemented within the framework of standardized, well-established operations, are important steps forward. For cities, the challenge is to transform existing urban environments to accommodate higher densities, while at the same time providing buildings that consume less energy. To achieve this, we can generate energy from sunlight using photovoltaic cells, for example, transform energy using heat pumps, and store it in the form of thermal capacity or in batteries. We can also look at the question of energy not from the angle of passive consumption by buildings, but through their active participation in the new modes of energy distribution that the smart city makes possible.

In your opinion, what are the most important levers for stepping up the sector’s energy transition?

A very important lever is to involve individuals and owners in the transformation processes. Public action can certainly facilitate these processes, but they can only be achieved through the active participation and investment of citizens, who might otherwise perceive transition as something “imposed” on them rather than as a necessary societal process. To increase their involvement, I believe that we should encourage ready-to-use energy solutions that are easy to activate and include understandable, transparent financial models.

In Denmark, there are 26,873 apartment buildings dating from before the 1950s, and around 43% of them have an energy rating of E or lower. Energy renovation of older apartment buildings thus provides significant CO₂ savings.

When it comes to improving energy efficiency, what are the best examples you’ve seen in recent years?

The Klimakarré development, in the Østerbro district of Copenhagen, is a flagship project in sustainable urban renewal and a showcase for how an old, obsolete square can become resilient and optimized in terms of energy use.

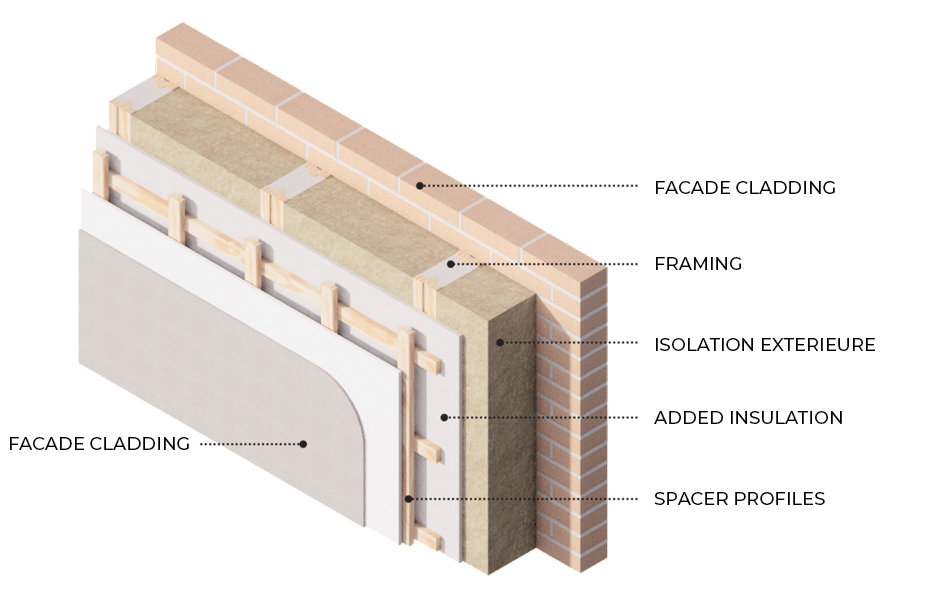

In practical terms, we deployed an exterior insulation solution developed for old apartment buildings. These buildings, dating from before the 1950s, are generally very poorly insulated. This leads to high energy consumption and a poor indoor climate. The solution used, Klimafacade+, reduces energy consumption while radically improving the indoor environment and quality of life for residents. Our goal is to see this solution widely implemented throughout the city in the years to come. It is important to note that this project is economically profitable, and also represents a model of collaboration between the city of Copenhagen, residents, owners, consultants and suppliers.

¹Sustainable construction terms:

The EPBD (2024 - Energy Performance of Buildings Directive of the European Union) is positioned as a key lever for making the entire EU building stock carbon neutral by 2050. It aims to reduce emissions and improve the energy efficiency of buildings on a large scale. The directive has a direct impact on the legislative framework of EU Member States.

The CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive), which replaced the NFRD (Non-Financial Reporting Directive) in 2024 by strengthening it, is a European directive on non-financial reporting. It requires large companies in the EU to monitor and report their performance in environmental, social, and governance areas. The CSRD introduces a concept of corporate responsibility that extends beyond economic performance.