7 min

7 min

Light, cheap, and modular, a thermal and acoustic insulator, and off ering excellent fire protection, gypsum has established itself as a must-have in the construction industry all around the globe. In most European countries, as well as the United States, Canada, and a number of Asian countries, recycling streams have been put in place for gypsum-based products.

A world on the move

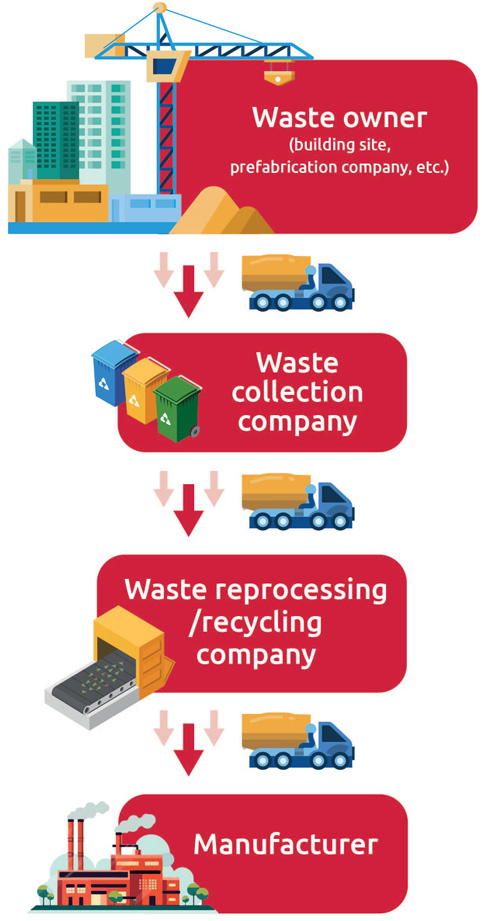

Because the recycling chain requires the involvement of many players, establishing a partnership approach between construction professionals, collection and processing companies is essential (cf. infographic). In Norway, a partnership between Saint-Gobain, the waste collection company Ragn-Sells, and the reprocessing equipment provider GRI offers actors working on building sites a service that handles the recycling of their gypsum waste and plays a role among decision-makers (architects, social landlords, etc.).

In certain countries, we are seeing the introduction of regulations that promote the circular economy for gypsum. In England, Germany, and the Canadian province of British Columbia, gypsum-based waste is prohibited from being sent to landfill. All around the world, the costs and constraints in this regard are increasing, which is encouraging a circular approach. In Italy, a decree stipulates a minimum recycled content for construction materials used in public projects: it is 5% for plasterboard. In France, since the Anti-Waste for a Circular Economy Law (Agec) in February 2020, the introduction of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for construction materials – a world first – economically supports recycling streams and sets ambitious recovery targets per stream. With this in mind, in 2022 Placo® launched the world’s fi rst plasterboard made from 50% recycled plaster.

What are the limits to recycling?Structural: If we were able to recover 100% of all gypsum waste sources, the recycled gypsum content in a board would reach 25% at most. This is because there is a limited amount, as the renovation or demolition waste corresponds to the volume of products put on the market 30 or 40 years ago, which is much lower than today’s figures. This stock will nonetheless increase over the coming years, due in particular to the renovation of buildings constructed at a later date.

Quality: Practices involving deconstruction and sorting at source during renovation or demolition operations are still rare. The waste to be reused is a mix of materials and the gypsum salvaged is often too contaminated to be used as a replacement for virgin material – even after sorting and treatment.

Industrial: Given its different physico-chemical properties than natural gypsum (density, presence of residual paper, etc.), the use of recycled gypsum impacts the manufacturing processes, particularly in terms of energy overconsumption, due to a need for additional water when producing the plasterboard.

Economic: In many countries, due to low landfill costs, recycled gypsum proves to be more expensive than the virgin material, and the transport, sorting, and reprocessing operations cost more than extracting the natural material. The economic rationale is even more significant in countries with coal-fired power plants, which produce an extremely economical synthetic gypsum from flue gas desulfurization.

Business model: The circular economy requires the creation of new collaboration models that are more cross-sector in nature and more complex to implement than mere purchase agreements.

The re-employment challenge

On the other hand, the re-use of plasterboard is virtually non-existent at present. The primary obstacle: the dismantling of a plasterboard by the book and its excellent condition required to give it a second life in a similar condition. This process is far from straightforward, bearing in mind that the plasterboard is integrated into a mounting system that has not been designed to be disassembled with a view to salvaging and re-employment. The board has been pierced with holes, screwed, jointed, etc. Moreover, a professional will be hard put to guarantee its mechanical and protective properties for further use, without knowing its past use or being certain of its preservation.

All the same, the re-employment of plasterboard is being studied. In the Netherlands, the company Juunoo is behind an innovative mounting system, guaranteeing clean dismantling thanks to a self-adhesive joint strip and grouting that come off easily after use. After removing the strip, the screws are completely visible, which facilitates dismantling from the wall without damaging the boards and encourages its reconstruction elsewhere at a later date.

But it’s above all upstream of projects that the re-use of gypsum needs to be considered. This is the case, for example, for the Athletes’ Village of the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games: the 60,000 m2 of interior partitions have been specially designed to be dismantled, and most of the materials will be re-used. They will enable the athletes’ rooms to be easily converted into accommodation and student rooms after the competitions. So, re-use is well on the way!

Recovery glossaryRe-employment: Allows an item that is not waste to be used again for the same purpose as that for which it was designed. Plasterboard remains plasterboard. This is the option often considered most pertinent for gypsum.

Reuse: Operation that offers substances, materials, or products that have become waste the opportunity to be used again, possibly in a different way than their initial use. What was once plasterboard is used, for example, to decorate a façade.

Recycling: Process by which the raw material from waste is used to manufacture a new item. Gypsum rubble becomes plasterboard.

Upcycling: Consists in salvaging materials or products that are no longer in use and turning them into materials or products of greater quality or utility. It involves recycling “upward.”

Downcycling: Recycling “downward,” for example when used plasterboards are sent to cement works to be converted into other materials. The gypsum can no longer be used and will therefore be lost.

Lean: This does not strictly speaking involves recycling, but there are substantial savings in terms of materials. The developer provides advance notice of the size of the plasterboards that it needs and the products are cut in the factory and then delivered, ready to be assembled with no alterations. There is no waste.

Photo credits: © Leonardo Briganti / Alamy © R.Demaret / Placoplâtre