5 min

5 min

When would you date the beginning of the Anthropocene2?

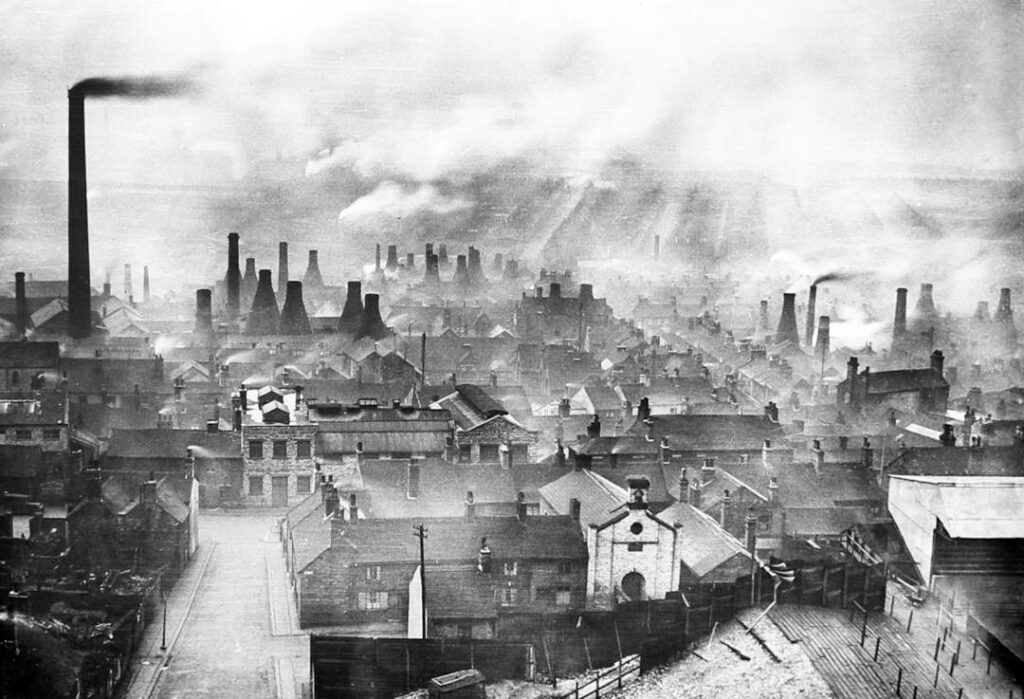

François Gemenne: I would place it at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, characterized by an acceleration in the use of natural resources, and therefore massive greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. This opinion is largely shared by the academic world, but I would point out that the subject is still under debate and must be decided by geologists, particularly the ad hoc Anthropocene Working Group for the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS).

Also read: How can cities be more resilient?

What are the specifically human impacts?

F.G.: The very idea of the Anthropocene – “the age of humans” – refers to human responsibility, to our place in the long history of the Earth, to the fact that we have become one of the main forces in the planet’s transformation. We long believed that we represented virtually nothing and that if we were to compare the history of the Earth to a 24-hour day, Homo Sapiens would appear shortly before midnight. However, the powerful message of the Anthropocene is that we have an impact on the Earth that will doubtless go beyond our existence as a human race. An impact on the climate but also on biodiversity, soil pollution, disruption of the water cycle, nitrogen, etc.

Climate change is one of the most frequently mentioned impacts nowadays…

F.G.: It is indeed the number one impact on the agenda, primarily because it requires international action and therefore quite sophisticated negotiation and cooperation mechanisms. Perhaps also because it seems to be the most pressing threat, which will have the most immediate repercussions on our everyday lives. As will loss of biodiversity, by the way, even if it doesn’t attract the same media attention.

Why do you think that urban areas are at the forefront of the fight against climate change?

F.G.: A whole series of public policies is essential in this fight, particularly policies linked to mobility and housing. It is cities – along with their 70 to 75% or so greenhouse gas emissions – that can activate these levers, as this is where most of the global population is concentrated. Another factor: we are currently experiencing a deep crisis in representative democracy. More and more people feel that their voice no longer counts in collective decision-making. Which leads to phenomena of mistrust regarding institutions. However, if we want to meet the climate challenge, it is important that we can act both as an individual consumer and a group of citizens. The city or community level seems to me to be particularly suitable, as people there are much more in touch with democracy and there is greater potential to catalyze energies.

What do you think of the concept of rethinking the city – reinventing the city in the Anthropocene era – and adopting a more sustainable approach to construction?

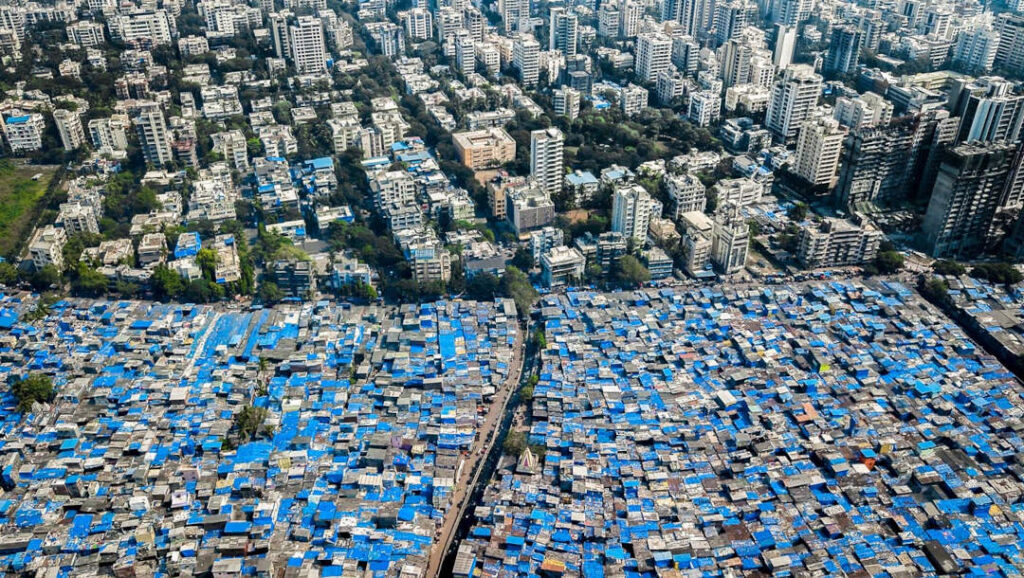

F.G.: It’s a critical issue, because cities will be welcoming more and more people and therefore concentrating a host of challenges and problems. Many development frameworks for the city, as it has been designed to date, are clearly not sustainable. Particularly rationales of urban sprawl and land take, inequalities between districts that subsequently pose a problem of equity when it comes to implementing decarbonization measures in transport or the construction of housing and infrastructure. In this respect, the building sector represents quite a considerable carbon footprint. In my view, in climate terms, two levels of power will be absolutely essential in the future: local and global. Yet we readily tend to focus the public debate on a national level, a scale that I think is less pertinent.

How would reducing inequality be an effective way to tackle climate change?

F.G.: More fully integrating the question of equity into measures to fight climate change is a must, both as a moral principle as well as for reasons of efficacy. If a measure is unfair or is regarded as such, it will be rejected by the population. Another important point concerns the question of vulnerabilities: the impacts of climate change will increase inequalities within a society. The most recent IPCC report highlights that an unfairer society is also more vulnerable to these impacts, whereas social cohesion is a major factor in resilience. Take for example two countries that are diametrically opposed economically. Bangladesh, a very poor society, has strong mechanisms of social cohesion and solidarity between its inhabitants, which make it a leading country in terms of adapting to climate change, whereas it is one of the most exposed to the impacts. In the United States, New Orleans owes the heavy toll of Hurricane Katrina (in 2005) – almost 2,000 victims – primarily to the very high levels of inequality that prevailed in the city and to the fact that many people were unable to evacuate in time or were even forgotten by the authorities.

Is urban renovation a solution to these inequalities?

F.G.: Clearly yes. Particularly in terms of city planning and organization, questions of transport or housing, for example. The problem is that few resources were allocated in decades of urban policies, little effort was made to “deghettoize” certain districts, and the feeling of being abandoned by the State and the public authorities remains very strong there. It’s not just a question of funding – the problem has often been reduced to this – but rather the way in which we consider urban policy and connections between different neighborhoods, especially between central and outlying areas. It is particularly important to work on housing policy, especially from the point of view of construction standards. Because the thermal renovation of housing will allow us to simultaneously aim for greenhouse gas emission mitigation and climate change adaptation targets.

The question of habitat really brings us back to our place on Earth both in terms of time and its long history and of space. The big climate change question is habitability: how are we going to inhabit the Earth?

[1] A political scientist and observer, Director of the Hugo Observatory (international environmental migration observatory at the University of Liège, Belgium) and member of IPCC’s Working Group II, François Gemenne is the author of numerous articles and works on climate change adaptation policies, including Atlas de l’anthropocène in 2019. His latest work, L’écologie n’est pas un consensus : Dépasser l’indignation, was published by Fayard in 2022.

[2] The term Anthropocene was invented in the early 2000s by the Dutch Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry Paul Jozef Crutzen. It means that, for the first time since humanity appeared, humankind has such an impact on the planet that it has become a force in its own right, a potential determinant of a new geological era.

Photo credits: © Eyeem/r o s l e y, © The Keasbury-Gordon Photograph Archive/Alamy, © Orbon Alija/Adobe Stock, © Johnny Miller